Englishmen are rarely seen in our quiet and deeply unfashionable corner of south-eastern France. Most of them flash by on the autoroute on their way to Alpine skiing. Occasionally there’s a crash or a jam, and GPS re-routes them through our village. I always enjoy sitting on my doorstep, watching the bewildered faces of tourists who thought they were heading for Geneva yet now find themselves in the back of beyond – or as the French say, au milieu de nulle part (the middle of nowhere).

Skiing apart, the English tend to stick to the France of the tour guides – the Loire, the Dordogne, Provence, Bretagne. Those guides rarely mention the Ain, the river that gives its name to our region. So I’m always surprised when an English name pops up locally. This weekend produced a corker.

A friend of my wife’s came to stay. They went off for a potter around Nantua, the town at the foot of the lake (photo above), a short drive from our home. The beauty of Nantua’s setting, shielded by towering cliffs, is sadly not matched by the town’s long-faded allure. For decades it was a grimy valley bottleneck for heavy goods vehicles heading to and from Italy through the Mont Blanc tunnel, an hour or so away.

Then they built what may be France’s most expensive bypass. You can just see the elevated autoroute disappearing into a tunnel through the cliff (left side, photo below). It’s an engineering marvel, towering on concrete stilts above the valley, a key artery linking Paris and Geneva. But no-one at ground level would call it pretty.

The traffic through town has thinned out considerably, yet for all its natural advantages – its lake, its cliffs, its forests - Nantua still struggles to escape its reputation as a backwater best avoided. Too many of its houses still bear the stains of 50 years of diesel fumes. A lot of its shopfronts are empty.

But the town offers visitors a genuine jewel. The hills you see in the photos above are the beginnings of the Jura mountains, stretching northeast into Switzerland. These hills were home to some of modern France’s most cherished warriors – the Maquis resistance of the Second World War. I’ve written before about the region’s pride in its mostly amateur guerrillas (photo, below), who took to the mountains and forests to lead the first stirrings of armed revolt against Nazi occupation and Vichy compliance.

In Nantua, there’s an excellent Museum of the Resistance, telling the story of the Maquis’s growth from rag-tag harassers to disciplined aggressors – and the terrible reprisals the Nazis inflicted on local civilians. My wife and her friend dropped by the museum on Saturday (I’ve been several times). They returned with a story I’d never heard.

The Ain, it turns out, was once home to an unlikely English hero: Dr Anthony Geoffrey Parker, a urologist from Brighton who had studied medicine at Cambridge (while also representing the university at boxing and making a bit of money on the side playing the Hawaiian guitar). An exhibit in Nantua’s museum displays the leather wallet of medical instruments that accompanied him to France when he boarded a clandestine flight into the Nazi-occupied Ain on the night of the 6th/7th July 1944.

Parker, who was known locally by the Resistance codename ‘Parsifal’, spent the rest of the war tending to wounded Resistance fighters while dodging German patrols in what he later described as “a sinister game of boy scouts in the forests of France”. His efforts earned him a Distinguished Service Order medal from Britain; the Croix de Guerre with Palm and Gold Star, and the Légion d'honneur from France.

But how on earth did an English expert in prostatectomies come to be running around the Ain and Jura with a pack of scalpels in his pocket? For much of what follows I’m indebted to the specialists of Urology News – a magazine that normally focuses on prostates, bladders, catheters and the like in articles such as last year’s “Management of Urinary Incontinence in Retracted Penis”. Three years ago a pair of enterprising urology historians – Jonathan Goddard and Jasmine Winyard – dug out Parsifal’s story. And quite a story it made.

His student days behind him, Parker/Parsifal searched around for a suitable job and was taken on by the French Hospital in Shaftesbury Avenue, London. It quickly became clear that his French was nowhere near as good as he may have suggested on his application. A crash course in le and la ensued. By the time war broke out in 1939, he had successfully established himself as a French-speaking London surgeon and was on hand to treat injured French soldiers who had joined the exodus from Dunkirk.

Like many other wartime doctors of his age (he was then in his late 30s) he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps, took a small arms course, was trained in unarmed combat and eventually deployed to North Africa. He accompanied British troops from there to Sicily and Italy, where he contracted jaundice and was sent back to London to convalesce.

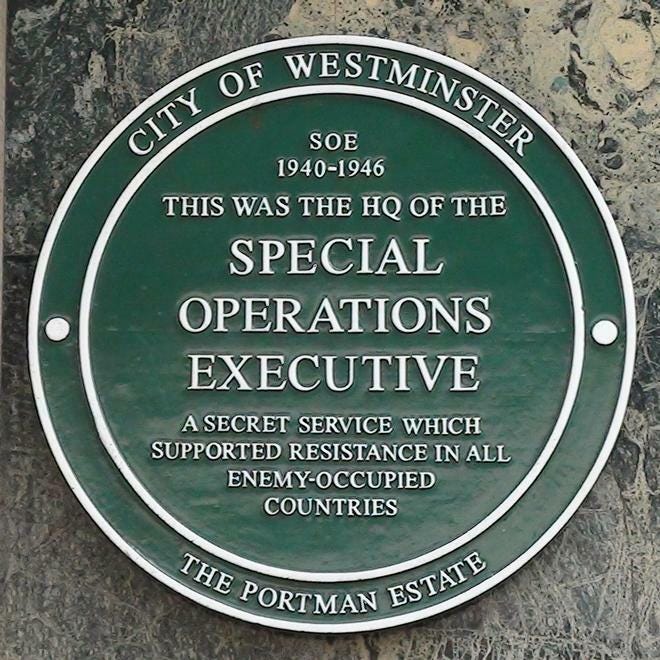

At home he was approached by the Special Operations Executive, then a secret Special Forces-style unit that variously became known as the “Baker Street Irregulars” (after the address of their London base) and the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare” (also the title of a new Guy Ritchie film) . The SOE was merged into Britain’s MI6 intelligence service after the war.

With his much-improved French, his military training and his surgical skills, Parker was an obvious candidate for a mission to the Resistance, which was desperate for medical help. The Maquis had to steer clear of regular French hospitals, where German guards were often waiting for wounded résistants to arrive. Parker was offered a pay increase of 10 shillings a day to join the Maquis of the Ain.

He duly parachuted into the Jura mountains from an American Air Force Dakota DC-3. The aircraft, stripped of all markings, flew on to land in a field in the Izernore valley, five minutes from our butcher’s shop. It was the first American plane of the war to land behind German lines; the feat is commemorated by a handsome plaque on the edge of town.

Parker spent seven months in the Ain and Jura, first setting up a field hospital in a former training school for workers in the local plastics industry; later moving to a former monastery then an abandoned farm. In 1991, 16 years after his death, a stone bench was dedicated in his honour at Crêt de Chalam, close to the remote mountain site of the farm he turned into his surgery.

After the war, Urology News reports, Parker became one of the first surgeons to try a new technique for prostatectomy, the details of which I wish I hadn’t read. He wrote a memoir – “The Black Scalpel” – and featured in the late M.R.D Foot’s 2008 book on the SOE in France.

To successive generations of French students of the Maquis, though, Parker will always be known as Parsifal – an Englishman who helped liberate the Ain.

Fascinating. And beautifully told. You've still got it, Tony.