Photo: Château de Bouligneux

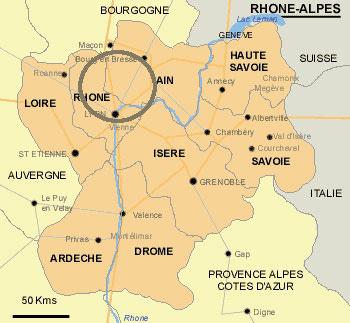

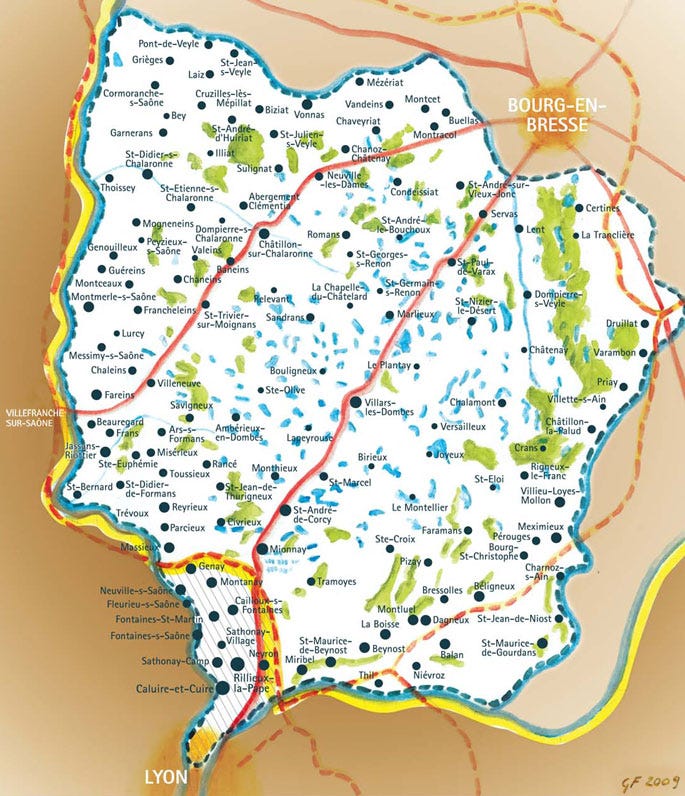

A few miles northeast of Lyon, away from the Rhone Valley and its guardian hills, lies a little-known area of France with a serious grammatical problem. It is formally known as La Dombes (singular), but its principal town is Villars-les-Dombes (plural).

I shall be taking up this matter with President Macron. Meanwhile, the Dombes (and they certainly sound plural) have become one of my favourite escapes from the mountains. In marked contrast to the jagged skylines to their east and south, the Dombes are almost entirely flat (a boon for ageing cyclists). They also possess a distinguishing feature that makes them unique in France.

Welcome to the land of 1,100 ponds.

The Dombes weren’t always a literal backwater. For centuries they were the subject of seigneurial squabbling as rival medieval barons laid claim to land that for much of the 15th century enjoyed the lofty status of a sovereign principality, ruled over by the Duke of Bourbon and the Lords of Beaujeu, among others.

Then King Francis I stepped in and confiscated all the land, turning the Dombes into a royal playground, handed down by marriage or inheritance to a parade of grasping aristocrats. At one point Anne Marie Louise of Orleans, aka the Duchess of Montpensier, traded all her land to the Duke of Maine (who I’m sure you’ll all remember was a bastard son of King Louis Quatorze), in return for the release from jail of her lover, Antonin Nompar de Caumont, the 1st Duke of Lauzun.

Still with me? I’m getting there, I promise.

As a result of these regal shenanigans, the Dombes began to fill with a rich array of splendid châteaux. In the early middle ages they tended towards the fortress model, with defensive towers built on man-made mounds to keep a long-distance eye on approaching armies.

Photo: Château de Montellier

Later on they started building sprawling HQs for wealthy farmer-landowners; ultimately they added lavish weekend getaways for Lyon industrialists and the like. Early on in this château-building spree, some duke or marquis or whatnot hit upon the idea of turning all those flat fields into shallow étangs, or ponds for breeding fish.

Bingo. France’s most productive inland pisciculture region was born. They are still hauling carp and perch by the netload out of the étangs de la Dombes, to the tune of 1,200 tonnes a year.

Photo: Fishing the Dombes. Daniel Gillet/ Dombes Tourisme [all other photos by me]

All of which brings me to one of the glories of the French cultural calendar, the annual Journées du Patrimoine – aka National Heritage Weekend. It’s the time of year when château owners across the country throw open their doors to allow the peasantry to ogle their medieval mansions, their suits of armour, their stuffed foxes and their Japanese harpsichords. In the Dombes this past weekend, we found three châteaux to visit. Road trip!

We started at the Château de Bouligneux (photo, top), an imposing pile of bricks that was originally constructed in the 14th century as a maison forte – stronghold. It’s a classic of its kind, an inner courtyard surrounded by high walls with a stunted tower (the top was demolished in the French Revolution on the grounds, apparently, that the aristocracy needed cutting down to size).

Photo: Front door, Château de Bouligneux

One of its wings remains a private home, which only survived the Revolution because local villagers thought it might make a useful farmhouse. It was returned to its original owners a few years later and unlike so many medieval fortresses in France, it has been continuously inhabited by the same family and never sold. Its current owner, a silver-haired gentleman with fine manners, showed us around. He apologised for the temporary absence of most of the chateau’s ponds, which are drained every four years or so to help the soil, allow a spell of cultivation and keep mosquitoes at bay.

Our next stop was the Château de Montellier, an altogether different beast. Unlike Bouligneux and most other châteaux of the region, Montellier was not attached to a village; its estate incorporated its own village, much of which was encased within medieval walls. Once again we were shown around by the owner, an affable gent who welcomed visitors not only to the medieval bits, but to his beautifully maintained family living areas (he failed to play us his Japanese harpsichord, alas).

Photo: Château de Montellier

Our host admitted, though, that maintaining his officially-designated Monument Historique was a full-time job – not least because ripping out the walls and ceilings to instal modern electrical, plumbing and heating systems was out of the question under French conservation laws.

It was while researching Montellier’s history that I came across a sentence which just about summed up the intricate arrangements of the French aristocracy, not to mention their obsession with unmanageably hyphenated names:

“Elie-Louis d’Entremont bequeathed Montellier to his niece Marie-Charlotte de Romilley de la Chesnelaye, wife of Guillaume-François-Antoine de L’Hospital, marquis of Saint Mesme, whose daughter Charlotte-Sylvie married, on the 9th November 1709, Claude-François-Joseph de Chevriers”. It carried on like that for the next three hundred years.

Our last stop was the Château de Joyeux, very different again in both size and style. Constructed by a Lyon silk manufacturer at the end of the 19th century, it’s a classic residential château presiding over an enormous estate of carp-filled ponds, formal gardens and extensive forestry. There’s a gatehouse the size of your average McMansion that has been turned into a gite (aka Air BnB).

Photos: Chateau de Joyeux and its interior

The Joyeux exterior is designed to be noticed from 20 miles away; the immaculate interiors are filled with the finest French fripperies. It’s more of a museum than any place you’d care to live in, unless you share Trumpian tastes in gilded chandeliers. But the gardens are lovely and it earned a forever place in my affections by providing me with the chance to photograph one of the most elusive of insects: a hummingbird hawk-moth (Macroglossom stellatarum).

The Journées du Patrimoine offer heritage minders a useful opportunity to rake in a bit of tax-free cash from admissions (they usually charge 5-10 euros a head), usually destined for restoration or maintenance projects. For the rest of us they offer a chance to compare the realities of château life with the fantasies peddled by popular television programmes.

Châteaux are certainly wonderful buildings to visit, but live in one? I think I’ll stick to my butcher’s shop.

i like the chateau of joyeux is it for sale