The road from Thoirette climbs away from the gorges of the River Ain to a green plateau bordered by forested hills and dotted with small farming villages.

I love this part of south-eastern France – remote, rugged, beautiful. I’ve ridden several thousand kilometres around these hilly roads on my bike; last year I embarked on a months-long project photographing ancient barn doors in varying states of surprisingly photogenic disrepair. I visited scores of villages around the region.

I was driving a few miles north of Thoirette on one of these barn door expeditions when the road turned sharply left at a sign for a small fishing business offering pond-reared trout, shrimp and frogs. Moments later I arrived at the tiny Jura hamlet of Anchay, a scattering of no more than a dozen houses, population less than 100.

There were no barn doors of interest in Anchay, hélas. Looking around I wondered why anyone would live there at all – it’s miles from the nearest supermarket, hospital, autoroute, train station, airport, whatever. This is truly what the French call “la France Profonde” – the agricultural heartland that is a coveted component of French identity, a part of the national soul rooted in rural mythology, where your nearest place of business really ought to be a shop selling frogs’ legs.

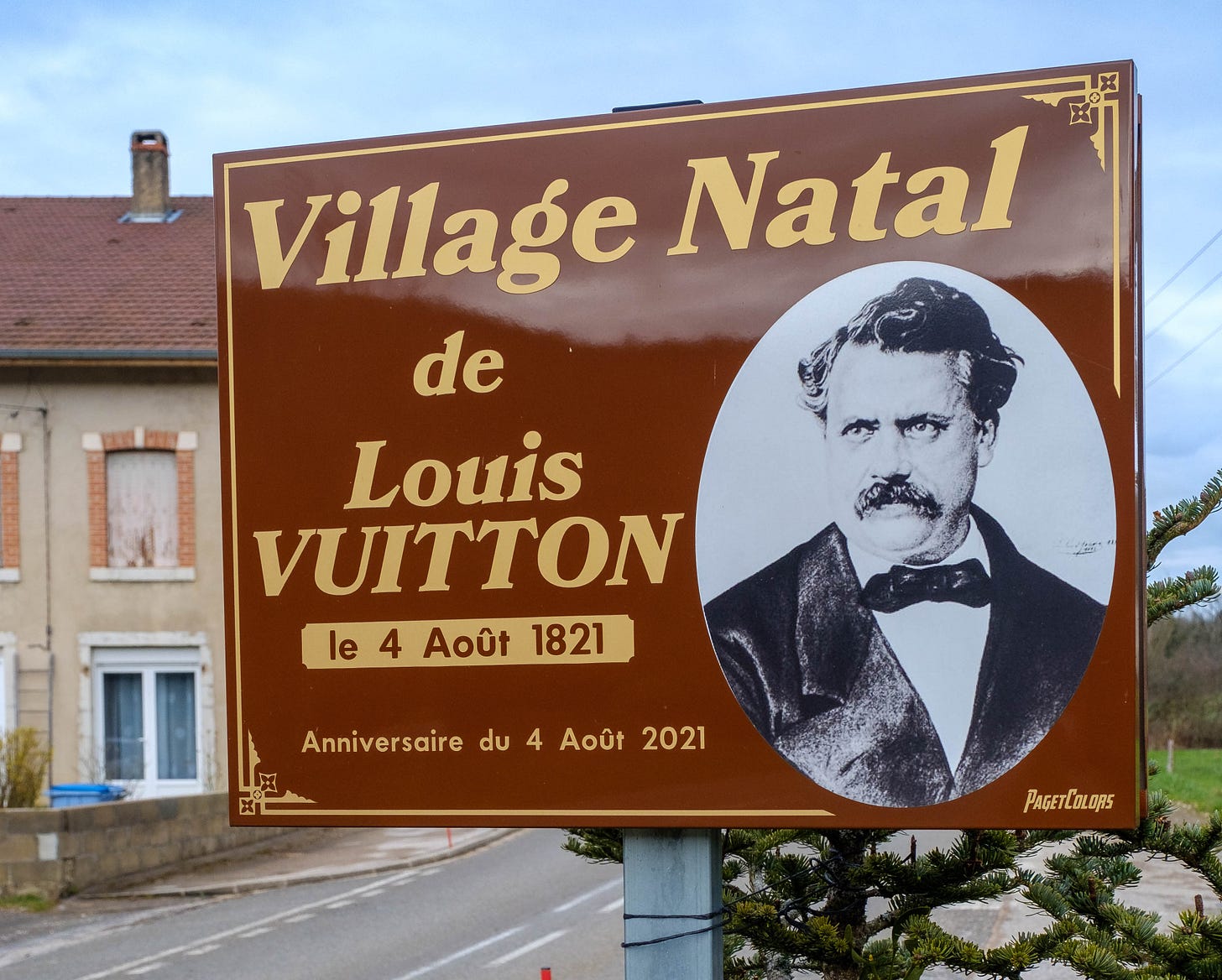

And then I noticed the sign.

Planted beside a potted Christmas tree, it bore the picture of a Frenchman whose name is a great deal more recognisable than his face. It is a name so famous it is written on the walls of buildings around the globe; its initials are engraved on some of the world’s most coveted luxury goods. Welcome to Anchay, the birthplace of Louis Vuitton.

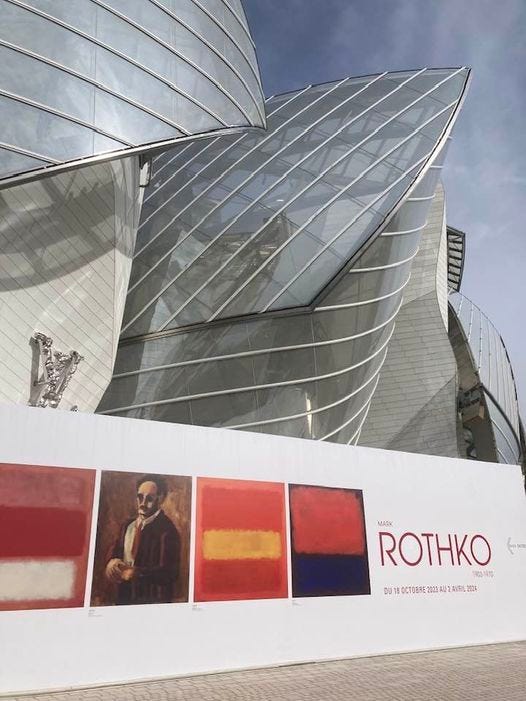

I had occasion last weekend to remember my visit to Anchay, and my subsequent research into Vuitton’s remarkable journey from a rural backwater of grim obscurity to the heights of Parisian style. Last Saturday I went to Paris to see an exhibition of Mark Rothko paintings – a billion-dollar assemblage of electrifying art on display in the French capital’s most beautiful or barmiest gallery (depending on your architectural taste).

Designed in apocalyptic style by the American architect-deconstructivist-maniac Frank Gehry (he of the Guggenheim in Bilbao, inter al), the $100 million Louis Vuitton Foundation is a very long way indeed from the humble rural watermill (photo, top) where the man it is named for was born. This cultural Mecca at the edge of the Bois de Boulogne has been variously described as a cloud of glass, an insect cocoon or an armoured caterpillar. There is nothing remotely humble or rural about it. As rags-to-riches fairytales go, Louis Vuitton surely takes le biscuit.

Photo above: SD Below: unidentified drone

Vuitton’s Anchay home was demolished years ago; only a small pile of rubble is said to remain. So how did he escape his rural fate to turn his name into a playground for billionaires? It somehow seems to me utterly perfect that this particular fairytale should begin with a wicked stepmother.

Born in Anchay on 4th August 1821, Vuitton lost his mother when she died giving birth to another child 10 years later. His father remarried within a year, but the new wife did not take kindly to her predecessor’s children. At the age of 14, Vuitton fled the family home on foot, seeking sanctuary from his stepmother’s cruelty at the Paris home of an older cousin, 500 kms distant. It took him two years to get there, walking and working his way across France, ultimately finding a job in the capital as an apprentice packer and box-maker. His employers served wealthy families who needed to transport their clothes and other goods from Paris apartments to country châteaux at different times of the year.

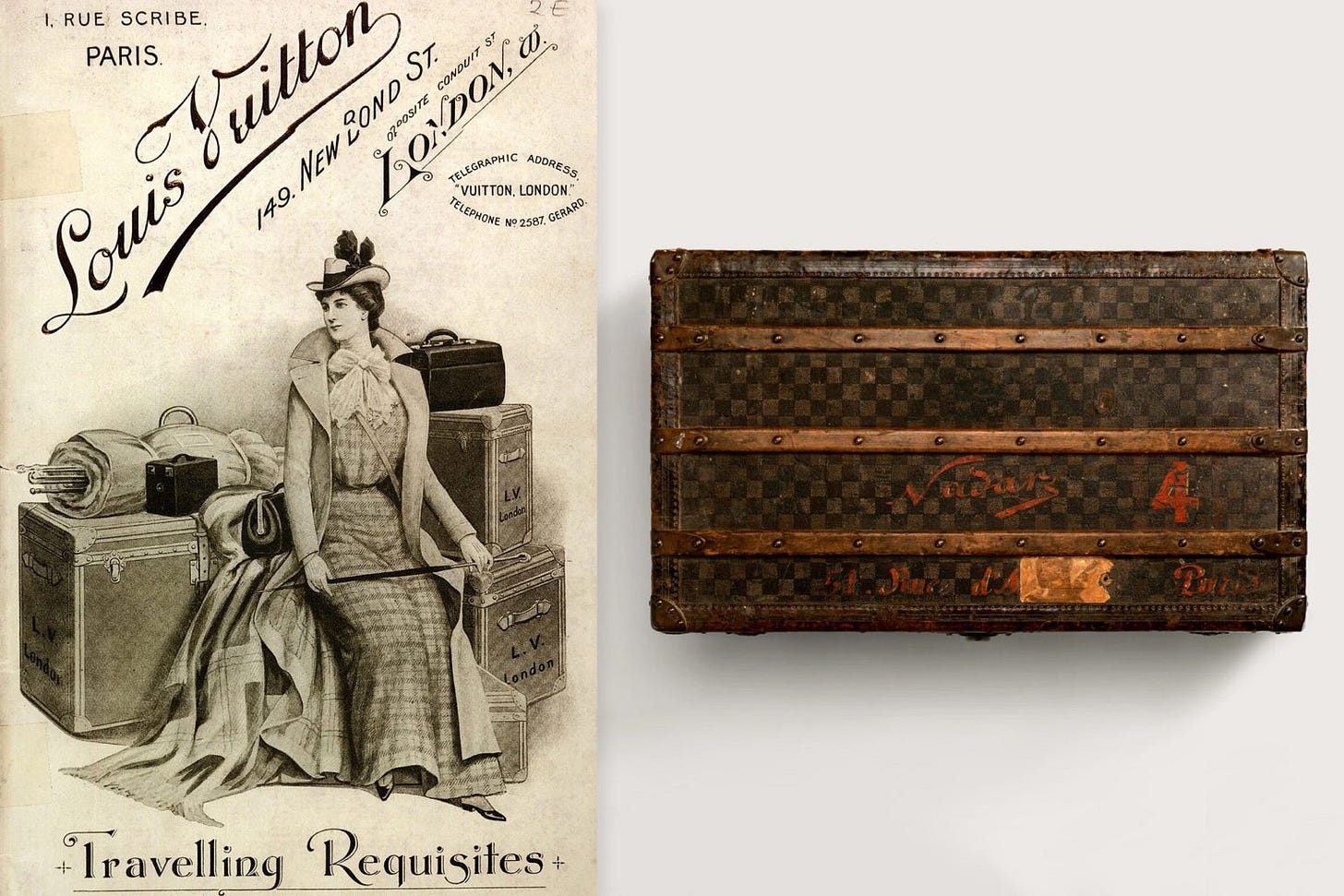

The rest of the story you can probably guess. In 1855, Vuitton married a Parisian heiress named Clémence-Emilie Parriaux. Her money helped Vuitton open his own shop close to the Place Vendôme. He hit upon a bright idea: instead of making disposable boxes for every journey, why not create solid, reusable containers?

The Louis Vuitton trunk was born and a factory was opened at Asnieres, a Parisian suburb. Among his early customers was none other than Doña María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina de Palafox y Kirkpatrick, 19th Countess of Teba, 16th Marquise of Ardales – better known as Mrs Napoleon III, Empress of France. Mrs Nappy – sorry, but I’m not typing all that out again – hired Vuitton to pack her for a visit to London, and his entrée to the French elite was secured.

Photo: Vanity Fair

Vuitton died in 1892, leaving his flourishing business to his son Georges. It was Georges who created, four years later, the LV monogram that became one of the world’s most enduring and desirable trademarks. The Vuitton business survived both world wars, though not without controversy. Several family members were accused of collaborating with the Vichy regime under Nazi occupation and one great-grandson of Louis became chums with the local Gestapo.

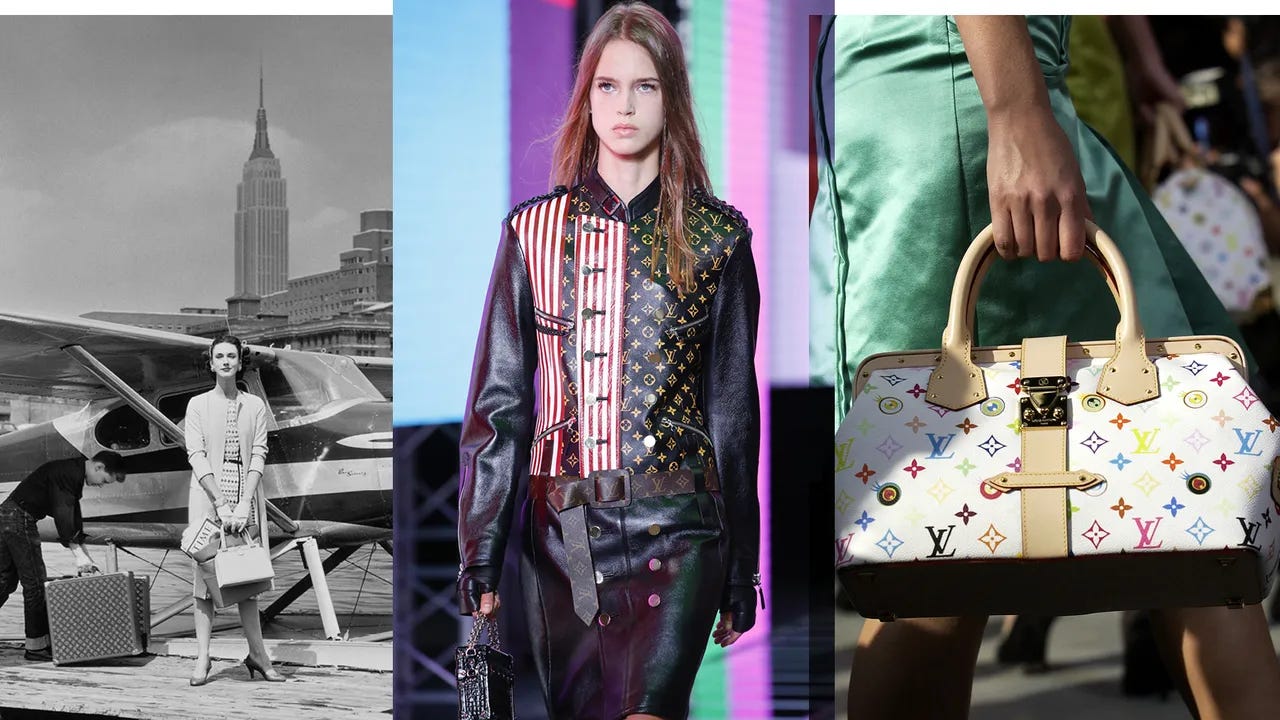

Photo collage: Vogue magazine

By the 1980s the company had become a multi-national luxury conglomerate and an icon of French excellence; in 1987 it merged with Moet Hennessy, the champagne and liquor titan, to become the world’s leading groupe de luxe.

When the Parisian businessman Bernard Arnault took control of the group two years later, LVMH expanded into shoes, watches, perfumes and God knows what else. Arnault rose to become (as of today) number one - the world’s richest man - on the Forbes Magazine Real-Time Billionaires List (he’s currently sitting on a $232.5 billion pile, streets ahead of those noisy losers Musk and Bezos). Next up in the LVMH plot for total world dominance: a Louis Vuitton hotel in a prime site on the Champs-Elysees (construction work currently hidden behind a giant trunk-shaped billboard).

So that’s the story of how I met Louis Vuitton (metaphorically speaking, you understand), but it comes with a small twist that is not widely known.

When Vuitton was born, there was a certain amount of confusion over his exact name: it appears as both Vuitton (two Ts) and Vuiton (one T) on his birth certificate. Both versions are to be found among family descendants in the Jura.

Not long ago, my wife was out walking the dog when she happened upon a memorial tablet at the foot of a hill only a few hundred metres from our home.

We live in an area that was rich with Second World War resistance activity – and numbed by the Nazi reprisals that often ensued. There are many tablets around here recording local atrocities, but this one seemed particularly brutal. On 19th July 1944, German troops raided a hospital in nearby Nantua in search of resistance fighters who might have been wounded in clashes with their forces. They took away nine patients, all nursing injuries. The tablet above our village records that the nine were “vilely finished off by the Teutonic hordes” - they were taken to the woods and shot. Among their number, one name stands out: Jean Vuiton.

I haven’t been able to confirm that Vuiton and Vuitton were in any way related, but I’m always moved by these war memorials. Some Frenchmen escaped the WW2 carnage, their fortunes intact. Others lost everything but their names.

click bait!!!!!!!!!