There’s a new mini-series on Netflix, based on an American novel set in France towards the end of the Second World War. The 2014 novel, All the Light We Cannot See, features a blind young Frenchwoman caught up in the battle for Saint-Malo in August 1944. Anthony Doerr’s multi-layered story won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction, was described as “hauntingly beautiful” by a New York Times reviewer, and was recommended by Barack Obama. My teenaged daughter loved it, mostly.

The Netflix series, on the other hand, was described by Time magazine as “a schmaltzy, incompetent, borderline offensive mess”. We watched it over the weekend and giggled most of the way through at its cartoonish depictions of nice Germans, nasty Germans, and the French Resistance winning the war.

Suffice it to say that the male French heroes are played by those least Gallic of Hollywood actors – Hugh Laurie and Mark Ruffalo. Laurie is a compelling presence as always but an Englishman playing a Frenchman whose only French words in the entire series are ‘Vive la France!’ invites all manner of ridicule. Ruffalo loses his American accent for some kind of bastard English mumble. (The German characters are played by German actors, speaking English with accents of varying menace. It all gets rather distracting).

The series revolves around its French heroine (bravely played by Aria Mia Loberti, a blind American actress in her first lead role). There’s an unconsummated romance and a bizarre diversion into Indiana Jones-style treasure-hunting. The novel’s shaded themes of darkness and light get lost in a black and white tale of bad guys chasing good guys while the good girl - well, no spoilers.

I mention all this because France’s experience of war is a lot more interesting than this dopy resistance fantasy suggests. The French have struggled for decades with the bitter legacy of collaboration. There was much to celebrate in the genuine heroism of a few résistants; much more to forget in the sullen acquiescence or traitorous connivance of far too many ‘collabos’.

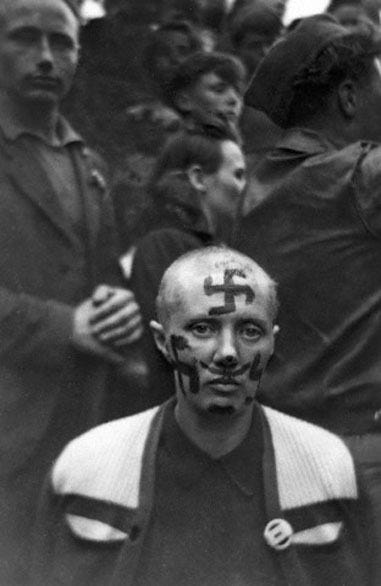

In All the Light We Cannot See, much of which unfolds during the Allied assault on the heavily fortified citadel of Saint-Malo, moral niceties are jettisoned in favour of the corniest clichés. Every French person we meet, with one exception, is a valiant résistant. The exception is a tart who sleeps with German officers and somehow knows in advance that when the Americans arrive she’ll be tarred and feathered then executed. But there was a lot more to postwar France than punishing errant tarts.

The Resistance has been on my mind of late as I explore the villages around our home in south-eastern France. With the remembrance ceremonies of November 11th approaching, I’ve been reminded repeatedly of the price this region paid for its defiance of German occupation.

The hillier parts of the Ain department, where I now live, were hives of clandestine revolt. There were maquis camps in the forests and spy networks in the towns. I have seen countless plaques on so many village walls recording the names of maquis rebels summarily executed or civilian residents shot by the Germans in reprisal for resistance attacks. What they don’t record are the names of the collaborators who shopped their Jewish countrymen to the Nazis; or the civilians who resisted the Resistance because they resented the reprisals it provoked.

The terrible divide in wartime French society, exacerbated by the cowardice of the Vichy regime, may explain why, after the war ended, only 17 French villages or towns were awarded a special Resistance medal for their communal defiance of the Nazi invaders (Saint-Malo is not among them). Of those 17 communities, three are small towns in the Ain. Two of them, Nantua and Oyonnax, are within jogging distance of my front door.

Today, Nantua hosts an excellent Museum of the Resistance, which should be compulsory visiting for anyone who struggles through the simplistic banalities of Netflix’s bafflingly awful show. But it is Oyonnax that takes centre stage in France’s remembrance of the Second World War. It was in Oyonnax that the maquis staged its most audacious exploit of the war. It changed the way Winston Churchill regarded the resistance, and gave France heroes of its own.

In the autumn of 1943, the maquis appeared of little consequence. After a year of German occupation, disjointed groups of refuseniks were scattered across the country, regarded by the Nazis as no more than an occasional nuisance. Among many others were the communists of the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans, the Armée secrète, the Confrérie Notre-Dame, the Jade-Amicol and Jade-Fitzroy networks and the predominantly rural maquis, who took their name from the rough undergrowth that provided ample hiding places on higher ground in south-eastern France.

Lacking firepower and military training, the resistance was at first dismissed by collaborationist Vichy officials as a bunch of terrorists and hooligans. The maquis were genreally regarded in London and elsewhere as a military irrelevance - despite Charles de Gaulle’s efforts to persuade his allies otherwise. Then a decorated World War One French army officer named Henri Petit – code-named Romans and known ever since as Henri Romans-Petit – decided that the time had come to put on a show.

Henri Petit, aka Romans

By October 1943 - one year into the German occupation - Romans had become the senior commander of the Armée secrète in the Ain department. He hit upon the idea of staging a march through a local town on November 11th – Remembrance Day for the dead of World War One. Romans wanted to show as publicly as possible that the Resistance was more than a disorderly rabble. He needed a town with a minimal German presence and local French officials who were sympathetic to his cause.

As it happened the chief of police in Oyonnax was also a résistant. It was duly arranged that the police would be busy elsewhere that day; that the local telephone exchange would be blocked; and that smaller demonstrations be staged across the region to keep the Germans guessing should they get wind of Henri’s plans.

And so a legend was born. On November 11th 80 years ago, Romans marshalled a force of 200 maquis, clad in new uniforms of leather jackets, green trousers and black berets. Many of them carried rifles previously used for hunting deer and wild boar. Descending on Oyonnax from their forest camps, they marched through the town in broad daylight, to a bugle accompaniment. They laid a cross of Lorraine – symbol of De Gaulle’s Free France – at the monument to the dead of 1914-18. By the time the Nazis realised what had transpired under their noses, the maquis were gone, melting back into the hills.

Several photographs of the march were taken. One member of the maquis shot some film on an 8mm movie camera. As pictures of the marchers spread, they became icons of reckless defiance, of courageous rejection of tyranny, of the qualities that had proved in such short supply as Vichy-led France succumbed to Nazi diktat.

The German occupiers responded in depressingly predictable fashion: one month after the march the mayor of Oyonnax, Paul Maréchal, and his deputy, Auguste Sonthonnax, were arrested by the Gestapo and shot. Other suspects were rounded up and despatched to concentration camps in Germany.

Yet the march proved far from futile. The pictures eventually reached the English and American newspapers. Churchill was persuaded that the resistance was not a rabble after all. He authorised parachute drops of weapons and supplies. By D-Day in 1944, the maquis had grown from 25,000 men to a force of around 100,000. The French had something to be proud of at last [the 8mm film of the march, taken by a maquisard named Raymond Jaboulay, was lost for a number of years but resurfaced in 1969. Advancing digital technologies enabled researchers to restore it to pristine clarity in 2021; it is now part of the resistance collection in Nantua’s museum].

Oyonnax remains as proud as ever today. On Saturday the town will mark the 80th anniversary of the Romans-Petit march with a re-enactment parade of volunteers dressed in maquis uniforms and carrying toy sten guns. Thousands of spectators are expected to attend. On the 20th anniversary in 1963, de Gaulle was guest of honour. President Francois Mitterand attended the 40th anniversary in 1983. Thirty years later President Francois Hollande turned up. This year President Emmanuel Macron was invited, but the word is locally that his aides don’t want him to attend for fear he might be booed.

Romans-Petit survived the war, He died aged 83 in 1980, in the hilltop village of Ceignes, a few kilometres from Oyonnax. His life leading up to that magnificent march would make a great Netflix drama. I only hope they find actors who sound as though they might be French.

i actually read the book first, i don’t believe in this television nonsense.