Every now and then, a routine outing turns into a treasure hunt. It usually starts with a tip or an invitation from a member of my extended French family, and before I know it, I’ve gone off at some demented tangent in search of a story that makes me smile, or cry, or want to write a blog piece, or all of the above.

I guess that’s what retirement does to you. Too much time for demented tangents. I’m no longer obliged to stick to the subject at hand (this is not necessarily a good thing). So here’s the story of the mobile pigeon loft (model above) that helped win the First World War.

It starts with a call from my nephew, Romain, a professional mechanic with a passion for vintage vehicles. He has arranged a visit to a remote country barn that houses one of France’s most remarkable collections of antique cars, vans and giant trucks.

It is not a museum, Romain tells me. It is not routinely open to the public. It is a private foundation set up by the descendants of one of the great names in French automobile history. Every now and then they offer private groups the chance to ogle their goodies.

Marius Berliet built his first car more or less single-handed in 1895. Two years later he produced another one. By 1902 he had bought a small factory in Lyon, and the following year turned out 300 cars.

The Berliet marque soon took an honoured place alongside Peugeot, Renault, Delahaye and Citroën as France began the 20th century as the world’s leading automaker. It was then producing three times as many cars as Henry Ford and his American chums. Berliet later diversified into vans that in 1914 became France’s go-to military platforms for troop and equipment transport.

By 1939, car production had stopped and Berliet’s name was synonymous with delivery vans, buses, trucks and heavier specialist vehicles such as fire-engines. At one point it built what was claimed to be the biggest truck in the world: the Berliet T100, a 100,000kg behemoth used to carry mining equipment across the Sahara desert.

Photo: Author with T100 by Maelys

Only four T100s were built; two of them died in the Saharan sands and were broken up for scrap; one of them was somehow dragged back from Algeria to the tiny French hamlet of Le Montellier, where the Berliet family created what they described as a Conservatoire – an archive of 80 years of Berliet vehicles, from 1899 until the brand was finally dropped after a take-over by the inelegantly-named (to French ears) Renault Trucks.

Getting into the Conservatoire today turns out to be a bit of a challenge. It only accepts bookings in advance by small groups. But Romain was determined to visit this motor Mecca only 45 minutes from our homes. So he put together a party of eight, and into the rural wilds we headed.

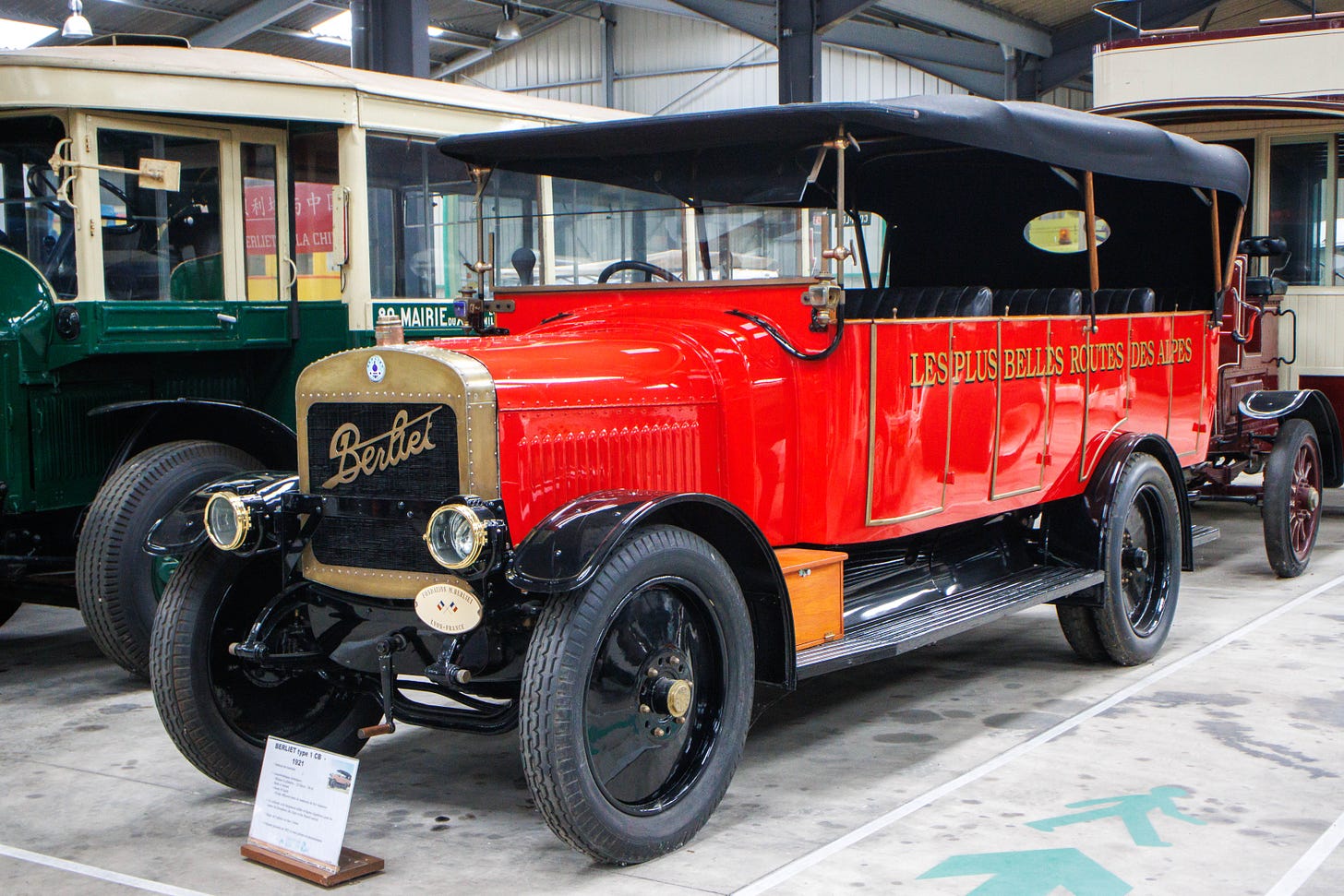

Suffice it to say, the visit was a triumph, a fascinating glimpse of French vehicular life down the decades, from early Berliet bangers to hefty utilitarians, many done up in their original liveries. I particularly liked the flame red Berliet bus that used to service Alpine resorts (“Les Plus Belles Routes Des Alpes”). And I liked too, the striking array of logos on vehicles from brands long dead and/or forgotten: Barron-Vialle, Cottin & Desgouttes, De Dion Bouton, Chenard & Walcker, Luc Court, Rochet-Schneider (which in 1932 produced an exceptionally comfortable-looking camping car, above). All this in an aircraft hangar-sized barn housing 250+ vehicles.

As luck would have it, though, the story that grabbed me most was about a vehicle that wasn’t there. A picture stood in its place. Our guide, a former Berliet manager (who didn’t stop talking for three and a half hours), gave us the rundown on Berliet’s most unusual van.

Only one model was made. It was a double decker, with the top floor converted into a carrier pigeon loft with 19 cages for 80 pigeons; the lower deck provided living space for the pigeon minder (the photo at the top of this post shows a die-cast metal model of the pigeonnier in question). It was sent into action in World War One as a mobile communications post, enabling officers in trouble on the front lines to send messages back to HQ in a hurry.

It wasn’t the only mobile pigeon loft in use at the time (the British converted a double-decker London bus for the same purpose). But the Berliet CAB Colombophile proved of huge value to military commanders, and spawned a host of smaller mobile pigeon units. By early 1918 the French army had conscripted 24,130 pigeons into its ranks; by Armistice Day in 1918 it was running more than 350 mobile lofts. The Germans started shooting not only the pigeons, but any French civilian pigeon breeders they could find. There’s a monument in Lille to both the pigeons and their breeders.

Photo: Good Morning Lille website

So why wasn’t this historic vehicle on display at the Berliet Conservatoire? The guide explained. The pigeons had played such a key role in the First World War, that the Berliet family felt the loft should be displayed in a public museum, not hidden away in a private collection. The loft is on permanent loan to the magnificent Great War Museum on the site of the WW1 Battle of the Marne near Meaux, not far from Disneyland Paris.

“This vehicle is a part of French history,” said the guide. “We only receive a few hundred visitors here. They have a million visitors at Meaux. Many more people can see and enjoy our pigeonnier”.

Photo: Musée de la Grande Guerre, Meaux

One day soon, I dare say, I shall happen to be passing Meaux.

Another triumph, Tony! So human an interesting. Have to tell you I most remember your piece (DT?) about the elderly and impoverished Armenian couple in Nagorno-Karabakh and her forgotten birthday.